The Space of Music: Carl Craig Interviewed by Joe Bucciero

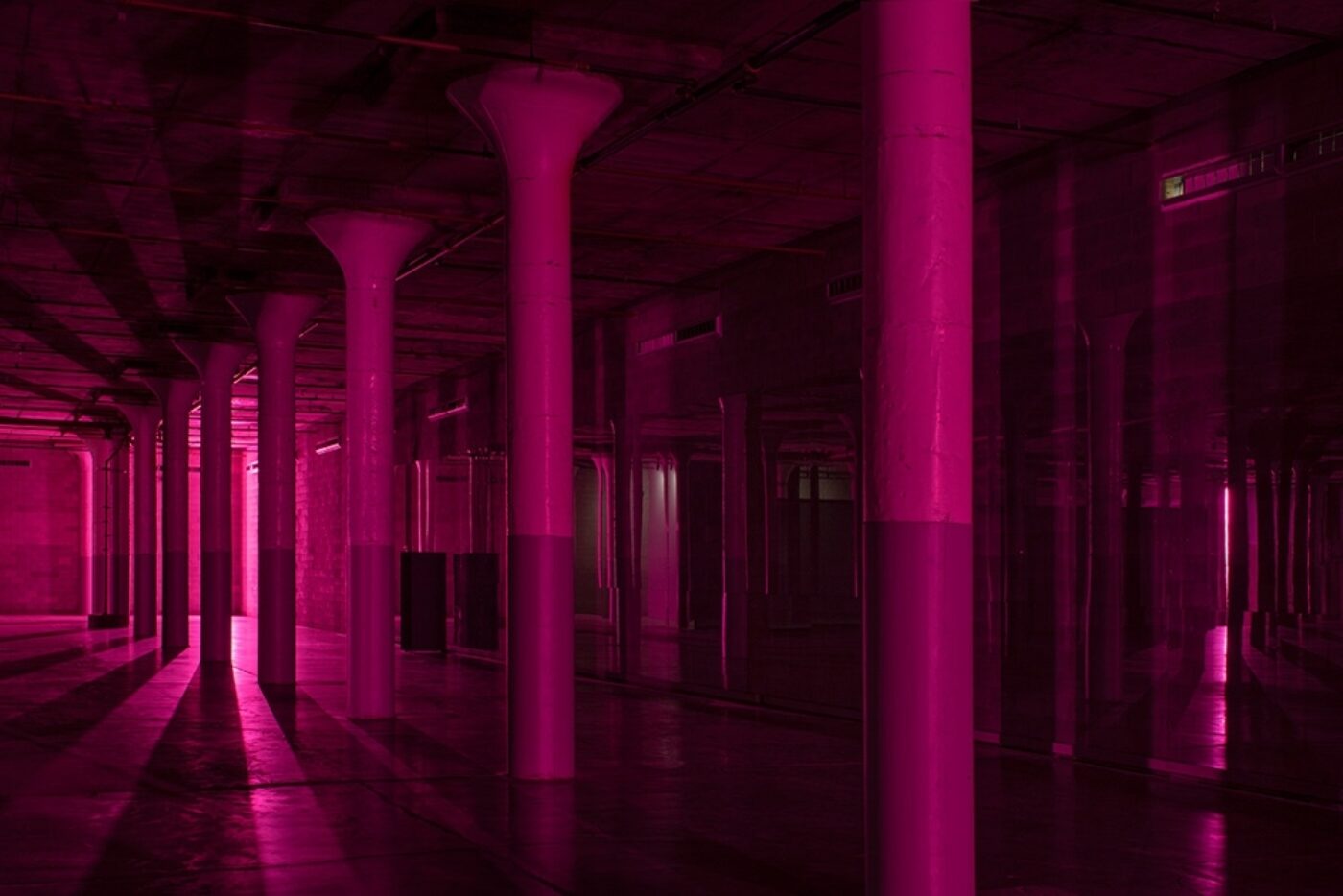

Party/After-Party, the first-ever installation by eminent techno producer Carl Craig, occupies a large room on the bottom level of Dia Beacon, the former site of a Nabisco packaging plant in New York’s Hudson Valley. Empty except for a matrix of large speakers, the room resembles a warehouse music venue, the likes of which have provided techno artists with sites for experimentation since the genre’s emergence among Black musicians and audiences in 1980s Detroit (Craig’s hometown). The institutional resonance motivated Craig to think through veiled realities that subtend techno and art more broadly: the artist’s life on tour, the audience’s expectations, the means by which events and installations are funded, executed, and preserved.

In our conversation, Craig reflects on Party/After-Party in light of these realities. He discusses music, too, of course: ranging from an array of formative influences that have guided his diverse productions of the past thirty years to the new, twenty-minute composition that anchors the Dia installation. The first half of the piece (Party) puts his stylistic heterogeneity on display: musical (and non-musical) ideas penetrate one another without losing a beat. The second half (After-Party) scatters the mix, providing a spectral array of noises that numb and provoke, simulating tinnitus. This juxtaposition reveals techno’s transformative potential to work both ways: euphoria, that is, cut with discomfort and isolation. The piece sucks you in, casts you out, then both at once; eventually, cycle after cycle, “party” and “after-party” seem to merge.

—Joe Bucciero

Joe BuccieroDia Beacon is housed in a repurposed factory, something Detroit has a lot of. There, it’s a reflection of economic fallout and related factors, but it has also provided space for artists to do their work and to perform to large crowds. I wondered if there were any particular spaces, or particular experiences with architecture, that you thought about when you were approached to do Party/After-Party.

Carl CraigAs far as architecture being inspiring to me, definitely. I own a Mies van der Rohe house. That’s been a really big deal for me—furniture design, things like that. Unfortunately there’s nobody in Detroit with money that has a vision to do something as amazing as what Dia’s been able to do. Having modern art in a warehouse space with the beautiful skylights is not on the front of anyone’s mind in Detroit and in many industrial cities. New York has quite a few people who have a lot of money, and it’s also at the forefront of the modern art scene. There are so many opportunities to do something in Detroit like what Beacon did, but I don’t think that we have the interest, we don’t have the education. The people who have that interest or education probably decided that they would be better suited living in New York, or Chicago, or LA. I hope with the renaissance that’s happening in Detroit now there can be some possibilities to open that up and to open up the minds of people locally who are art lovers and would like to do something that’s the next level for Detroit. Dimitri Hegemann from Tresor in Berlin wanted to open an event hall/club here in the old Fisher Body Plant factory, and he was declined. I don’t think they saw the vision, because nothing like that has been done in Detroit. Whereas in Berlin, it’s done all the time, or in London, in Paris. But to do that in Detroit is just something that’s alien to most people who are funding it.

Installation view of Carl Craig: Party/After-Party, Dia Beacon, Beacon, New York. © Carl Craig. Photo by Bill Jacobson Studio, New York. Courtesy of Dia Art Foundation, New York.

JBThere’s been more music- and sound-related material in museum and gallery spaces in New York for sure, whether a concert series like MoMA PS1’s Warm Up or your exhibition—something built around a musical artist, sometimes with visual components, sometimes just sound. Obviously the museum experience is very different from the club. It’s a different time of day, different modes of attention being engaged. What can you do at Dia, musically, that you couldn’t do on a record or in a DJ set?

CCThe After-Party part of the installation is me presenting the experience of having tinnitus. In the middle of a club set you can’t start putting on a high-pitched tone (laughter) and white noise, Doppler effects for ten minutes because people would not understand what it is. But because there is a story behind this, I can do that. The Party is a composite of all the experiences of me traveling around the world—to different clubs, different kinds of music. All that stuff is put into a system, which is a multichannel system instead of just a stereo stack. There are multi-stacks that have two channels per stack, and I can apply different sounds to those stacks; when I play live, that’s not possible. Playing for two hours in front of a crowd, there’s a certain momentum that you want to give to people, and then there’s a certain amount of momentum that people expect as well.

JBEDM—more than just techno—is often connected to feelings of euphoria, whether that’s through drugs or through loud, repetitive music and the communal experience of dancing. But you’re looking at the other side of that—the fallout—filtered through your own personal experience.

CCYeah. If we would’ve come at this project as just being a party, it would say something else. Somebody who comes to enjoy a performance, like when Moritz von Oswald and I played together at the opening of Party/After-Party, is one thing. When someone walks into a gallery and there’s a party going on, that can be really cool for people, but it could be a bit Disney, because it’s like, “Oh, yeah, I went to that party yesterday”; “I went to that party last week.” Doing the After-Party and the Party together, it’s a whole other experience, a whole different level than going into a bar where there’s a DJ and turntable set-up, or you go to Coachella to the dance tent, or you go to Ibiza.

Installation view of Carl Craig: Party/After-Party, Dia Beacon, Beacon, New York. © Carl Craig. Photo by Bill Jacobson Studio, New York. Courtesy of Dia Art Foundation, New York.

JBYou have this very close attention to history, both your own, with reworking your tracks, and also the history of music, which comes into your work through DJing but also in interviews, when you often talk about influences you’ve had. How do you think about this history, and does it have any bearing on this project?

CCHistorically, my interest is in jazz, from after bebop up until fusion and stuff like that. I was highly influenced by Miles Davis and music that was coming out in the late ’60s and ’70s, including Parliament Funkadelic, as well as the electronic stuff that was coming from groups like Kraftwerk.

JBDia has a Minimalist tradition—Max Neuhaus, La Monte Young, Marian Zazeela—that is also rooted in the ’60s and ’70s. I know you’ve referred to Steve Reich before, another artist from that wider movement, but I wonder about your interest in this more Minimal, even meditative music.

CCI have a lot of interest in that, even someone like Harry Bertoia. He wasn’t a musician, he wasn’t necessarily making music, but he was making a soundscape that was amazing to me. You build your own work of art and play it. And put it on a record! That was a huge influence on me, as well as Steve Reich—and Steve Roach.

Installation view of Carl Craig: Party/After-Party, Dia Beacon, Beacon, New York. © Carl Craig. Photo by Bill Jacobson Studio, New York. Courtesy of Dia Art Foundation, New York.

JBSome of your peers from Detroit—like Jeff Mills and Derrick May—have also brought techno into different spheres, different music and art venues, stretching what can be done with the form. You once called “Papa Was a Rolling Stone” a techno record. Which makes me wonder, what can the word techno encompass? What does it have to leave out as it goes through different changes?

CCTechno is about attitude. It’s like how rap music is about attitude and lifestyle. Punk was about attitude and lifestyle. Techno is really about an attitude because we don’t lock ourselves into only listening to techno all fucking day long. The attitude of techno is that kind of brashness, but that you’re doing something that can sound like it’s timeless, and also that it’s not from this earth. That’s what “Papa Was a Rolling Stone” is to me; at any point I can hear it, and it’s just the amount of space that’s being used, the grooves. It’s got a groove without playing a lot of notes. It actually probably has more of a Miles aesthetic: it’s not about the notes you play but the notes you don’t play. The amount of space that’s in between bass riffs, or that there’s a little bit of Rhodes, and there’s some horns with an effect on them. The thing that’s carrying it is the hi-hat and the low bass. So, that is really techno to me.

JBIn an interview about your 2017 album Versus, you said that you wouldn’t call the record “techno-classical” but rather “action and adventure,” which is great. I wondered if you had any specific concept or framework for what this is. It’s an art installation, it’s techno—what is it?

CC“Action and adventure” is perfect.

Carl Craig: Party/After-Party is on view at Dia Beacon until the summer of 2021.

Leave a Reply